Public Speaking Report 2: The Six or Seven Types of Stories (Part 2)

When we left you last month, we had just shared the half-dozen or so types of stories that have endured for millennia. We also had given you the pieces of a narrative puzzle, hopeful that you would create a story of your own. So just how did you link the plot, structure, your main message, and the goals and values of your audience?

- Did you pick the plot that best fits your key points?

- Do you have a story that will resonate with your audience?

- Is your message coming through loud and clear?

Let’s get started on taking your story to the next level.

Chapter 7 – Where does my story fit?

As you learned in Chapters 1 to 6 in Public Speaking Report 1: The Six or Seven Types of Stories (Part 1), when it comes to presentations, the most effective stories are emotionally engaging, follow familiar plots, reflect your key message, align with an audience’s goals and values, and can come from anywhere – your own life or the world around you.

Now that you have your story, there are a couple of questions you must ask yourself:

- How am I going to incorporate my story into my presentation?

- Am I going to tell more than one?

A story can lead your presentation, end it, or be woven throughout. You also may tell more than one story. Just make sure each story reinforces your larger message. Furthermore, try not to be the sole character in the room – there’s no need to be the hero in every tale.

Here are a few suggestions:

Sharing Your Story – Tip No. 5

(You can find the first four tips in Public Speaking Report 1: The Six or Seven Types of Stories – Part 1)

Open your talk with a story, as opposed to, say, a statistic, a rhetorical question, or show of hands. Perhaps there is some sort of gap between you and your audience, or you want to share a life lesson but not come off as preachy. In her book, “The Story Factor,” Annette Simmons writes that stories provide a more accessible route. A story, she says, is a “more dynamic tool of influence. Story gives people enough space to think for themselves.” If you haven’t come up with one of your own, there are well-known fables, allegories, and parables that you can borrow and adapt to your key points. Here are some examples:

- There’s a gap between you and your audience — You could share a story about two political opponents who came together for a common good as a way to show how it’s possible to shrink the gap.

- You want to share a life lesson — You are talking to two community groups about a new neighborhood plan. You want them to get behind it, but they keep arguing over small details. You are trying to warn them that this bickering threatens to derail the project. You could share a fairytale about two warring tribes whose decades-old grudge kept them from noticing the rise of an even greater enemy.

End your talk with a story, but be careful while introducing the anecdote. In other words, a seamless transition transports your audience into the narrative without a clunky transition. Here are a few examples:

- “I just shared with you several obstacles we face in moving forward with our vision. There’s another organization that was up against seemingly unsurmountable odds and this is how they solved it …”

- “You may wonder how instituting these new policies will take us from No. 3 to No. 1 in our market. There’s no need to imagine, as a similar strategy helped this underdog company …”

- “We often believe we are just one voice in a sea of opinions. But every wave starts with a ripple and here’s where one ripple began …”

Weave your story throughout. You’ve seen this technique with comedians when they perform a joke at the beginning of the set and then reference it intermittently throughout their performance, or only return to it at the end. A speaker also can introduce an idea, reference, or story at the beginning of their talk that is referenced as part of each main point and then, again, at the end. Here are some ways to incorporate this technique:

- Break up your story into three parts that correspond to three main points.

- Start with your story at the beginning, make a reference to it in the middle, and return to it at the end.

- Introduce a mantra, adage, or truism that is the kernel of your story and strengthens your key point. You then sprinkle it throughout for emphasis. Here’s an example:

You are a local senior care coordinator and you are talking to seniors about the importance of getting out of their homes and remaining socially active. Your key message is this: New experiences lead to new connections and a healthier outlook on life. You share a story about a time when you were in a new city without a network of friends or family. In isolation, you became increasingly depressed. That is until you began living these four words: “The recluse is loose.” You can return to this catchphrase several times, uttering it as verbal punctuation for every point you make in service to the one key message.

Use multiple stories. Sometimes, small vignettes can be teamed with each of your main points throughout a presentation. Perhaps you are a sales technology representative and you are explaining a software suite to a potential customer. You have identified three main points: it increases productivity; it can quickly compile information from multiple departments for in-depth reports; it comes with round-the-clock support. For each point, provide an anecdote of a client who has benefited from that particular feature.

Chapter 8 – What is the theme of my story?

If your plot is all the places (main points) you hope to visit with the audience, then the theme is the actual route of how you will get them there. Your map needs to be clear, useful, and full of signs that point them in the right direction – to your main message.

Are they going to get there by you winning them over? Will they be moved from inertia to action? Is the journey one from lack of knowledge to comprehension? Are you going to take them from reality to imagination?

Sharing Your Story – Tip No. 6

Here are some story themes to consider:

Earning trust – If you are talking to a group that does not support your central idea, your story could have a theme that speaks to that opposition but also provides a path toward accord. For example, you could start with an open that clearly highlights your differences, then move into a story about chipping away at those differences. Your final story might be a tale of two disparate groups that realized peaceful resolution.

Sharing wisdom – Fables and analogies have long been used by speakers to delve into moral lessons and insights about human behavior, all without sounding too heavy or preachy. You can use that approach with a personal tale. Perhaps you are bringing a situation, challenge, or idea to a group that lacks awareness or deep knowledge of the topic. You don’t want to appear condescending so, instead, you share a personal account with a theme of how you once lacked the knowledge to tackle the challenge. You might develop three main points that reveal each tool or insight you learned at each step. The final chapter in that story is the realization that such tools are also available to your audience.

Imagining the future – Perhaps you want your audience to buy into a plan that is early in its process. Say you are the transportation director for a city that needs to do major construction and renovation to your commuter hub. While the overhaul is under way, traffic is going to be a nightmare and the construction will be costly. The changes, however, will make life easier. You might offer a story with a cautionary theme. What might the city look like if the plan isn’t approved?

You might offer this anecdote in your open:

“There will come a morning in the not-so-distant future when you will find yourself completely stuck – and I mean completely stuck – in your car for a good half hour as you make the half-mile trip from downtown to the train station. You know why that is going to happen? That’s because our current commuter hub is a congested mess with too few entry points and too many vehicles trying to get in. If you think it is bad now, just wait for the thousands of new commuters that will be moving here in the next few years. We won’t be a transportation corridor; we’ll be a transportation coronary.”

Counterintuitive – You are in a brave new world, thinking outside of the box. The main character will do something against the norm because no one told her she couldn’t. This theme could work well for a particularly vexing puzzle or support for an innovation that aims to resolve an intractable problem.

Chapter 9 – How do I refine my story?

Visual cues help us to better retrieve and remember information, or, in other words, your key message. So, you’ll want to create stories that are descriptive and emotional, and that fire up imaginations. If you succeed, the audience will conjure up mental images they will attach to your words and create the cognitive best friends that will be hard to part long after your talk is over.

Sharing Your Story – Tip No. 7

There are several elements that make a good story a great story. Here are a few:

Be descriptive and concrete – The material needs to paint a vibrant picture. Here are two examples of the same passage:

Abstract:

“Yesterday, during a trip to the grocery store, I was reminded of the generosity of strangers and the simple things that can turn a day around.”

Concrete:

“It was meant to be a quick trip, some milk and a dozen eggs – and the candy bar I tossed on the belt at the last minute. The cashier swiped all items, dropped them in a bag, and said ‘That’ll be $8.38.’ It was $8.38 more than what I had, because, you see, I suddenly realized I had left my wallet on my kitchen counter. I was going to have to do this all over again, and that meant squeezing in a half hour errand on a day I did not have an extra half hour. As I went to gather my items, the man behind me handed the cashier a $10 bill. He said, ‘I hope someone would do the same for me.’ “

Utilize literary devices – Writers have a deep toolbox. There are many tools to amp up your story. Here are a few:

- Foreshadowing – Offer your audience a hint of what is to come without spoiling the suspense. (“This is an important lesson to learn. As you’ll soon hear, I, unfortunately, figured it out the hard way.”)

- Hyperbole – Emphasize a specific point by using exaggeration. (“I’ve learned nothing good comes of working 24/7, except maybe the knowledge that nothing good comes from working 24/7.”)

- Paradox – Contradictory ideas come together to reveal an insight that might take a while to understand. (“Less is more.”)

Don’t skimp on the details – Anecdotes work well if they are rich in details and meaning. An abstract retelling means the message lands with more abstraction. Rich details help your audience to imagine concrete pictures and scenes, which will help them to remember your key idea. An excellent example of this is Mark Bezos’ 2011 TED Talk. Bezos, a volunteer firefighter and member of the leadership council of a New York-based nonprofit called Robin Hood, used rich details to enliven an old adage.

Be vulnerable – Share the details that symbolize a larger truth, bring about an epiphany, or radically change a perspective. If these have happened to you, such disclosure can boost your connection with the audience.

Lead the way – Make sure that your story has a point. It needs to answer the question, “So what?” that your audience will be thinking. Sometimes, the story speaks for itself. If, however, you think the audience might need a bridge from the story itself to the moral of the story, there are alternatives to having to say: “Listen up, here’s the point of the story.”

Here are a few:

- “That’s important because …”

- “What does that tell us?”

- “That example taught me that …”

Your overall approach should be a seamless passage from the story to the main point you want it to convey.

Sharing Your Story Tip No. 8

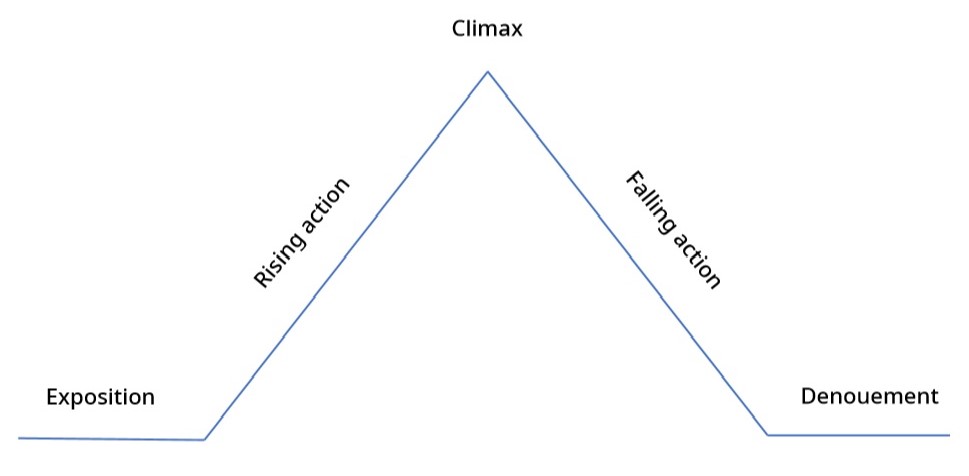

As you refine your story, you can see if it is following the five elements of a narrative arc that help to build tension and keep listeners hooked.

We spoke about these in Part I, but here they are again:

Exposition – The reader is put into the story. Characters are revealed and developed. The scene is set. The conflict is revealed.

Rising Action – The pace picks up, as challenges and obstacles begin to get thrown before the main character. Conflicts build and complications arise.

Climax – This section signals the turning point. The suspense that has been building peaks and fallout is imminent.

Falling Action – The story begins to fade into the sunset. Mysteries are solved (or left unsolved) and fictional strings are tied up.

Denouement or Resolution – It’s time to take a breath and reveal the outcome of the story. The hero returns, the hero is transformed, or the main character is banished, for instance. This is the place an author may reveal a moral or lesson.

As an example, let’s return to the senior care coordinator who was talking to seniors about the importance of getting out of their homes and remaining socially active. We covered where she could place her story in her presentation; now we’ll use her story to show how to incorporate those five elements and keep her audience hooked:

Exposition

“A big move to a new city. A new, stressful job that wasn’t what I thought it would be. No friends. No family nearby. No hope. My new life was transforming me into something I never wanted to be. I was turning into a hermit.”

Rising Action

“Every morning I had even more bags under my eyes than the day before. My aches had aches. My toned muscles were beginning to mutiny. My skinny jeans had given way to stretch pants. I was gaining weight. I was depressed. I was heading toward a bad place.”

Climax

“One night, as I caught myself in my hallway mirror, I did a double-take. Where had that dynamic 45-year-old gone? Was I just going to let myself slip away? I was. I headed for the couch. Then, four words snapped me back to my reflection. This is what they told me: “The recluse is loose.” Before I could argue them away, I grabbed my sneakers, walked out the door, and began to explore.

Falling action

The next night I went to a program at the library. The following evening, I went to a movie with my coworker. And so it went for the next several months. Then, it stretched into years.

Denouement

My days of isolation and sadness are over. I don’t go out every night, but I make sure that my life is filled with new experiences, new connections, and new outlooks. They are there for you, too. You just have to open the door.

Chapter 10 – How do I show my story?

Your body is a crucial co-author in your tale. Any presentation benefits from effective body language, but a story really lands when what you are saying is strengthened by how you are saying it.

Sharing Your Story – Tip No. 9

Inhabit the character – If you feel confident enough to take on the mannerisms of each character, you can bring them to life by altering your voice – how high, low, fast, or slow you go – and adjusting your posture. In other words, no hero poses if you are portraying a character who is a bit down on his luck. There’s no need to stage a one-person show, by the way. If you feel confident, you can certainly go big. However, even subtle gestures and mannerisms can move a story along – sometimes even more effectively than grand gestures.

Create distinct spaces – In general, speakers are encouraged to move when giving a presentation. With a story, try establishing a different spot for each character and move to that spot when speaking in that character’s “voice.” It may help the audience to better remember the characters, which helps them remember the story, and, ultimately, your message.

Gesture – Use your hands as stand-ins for descriptive details. Was a building “way high?” Well then make the span with your hands. Did you knock on a door to be let in? Well then, create that invisible door and rap your knuckles across it.

Facial expressions – Making direct eye contact is an effective tool to build a connection with your audience. You also can use those eyes (and brows) to register surprise, show fear, or evidence doubt. Expressions allow you to paint a better story.

Pause – Allow for breaks of laughter or moments to let important points sink in. Pause to set up a surprise or a shocking ending.

Chapter 11 – How do I practice my story?

You may be saying, “I am not an actor. Can’t I tell my story from behind the lectern?”

You can. There are some stories that are so powerful and speakers who are so engaging that a more stationary perch does not take away from the experience. With the right gestures, expressions, and vocal cues, a story can come alive even if you are rooted behind a mic.

It’s just this: You have reduced the number of tools you have at your disposal to convey it. Unless there is a reason to be there, why make it harder on yourself?

Movement brings a dynamism to your delivery that can really engage your audience. Give yourself plenty of opportunities to practice the story (or stories) you plan to share before your next talk. A successful delivery includes the right timing, the right look, the right nonverbal and vocal cues, and the right energy. That comes together with practice, so you can deliver when it’s time to present.

Here are some next steps:

-

- Find a practice audience or tape yourself

- Ask for feedback

- Constructively critique your performance

Then, ask yourself these questions:

Sharing Your Story – Tip No. 10

Am I getting my message across? The story or stories you share need to serve the message or key points.

How’s the length? As with any page-turner, the action needs to move quickly. Cut the places that don’t work or drag. And, remember: If you are going to go on at length with a story, that punchline – or main point – better be a good one. In other words, a pithy insight after a 30-second tale is a good investment. A deep revelation is a proper ending to a two-minute tale. But a breezy adage following a five-minute story might stretch your audience’s patience for what you have to say next.

Too many voices? Perhaps a narrator is a better bet than a handful of characters, particularly for a shorter story.

Do I appear authentic? Your story should never feel forced. A great story that is not great for you is, in the end, not a great story. Still, challenge yourself and expand your range. Test your storytelling ability. Too often, we retreat to stories that are natural for us. Authenticity will develop when you have done the work to prepare and practice for your presentation, and gain the comfort to deliver it.

Do I need a dress rehearsal? Yes! Do at least one run that is close to the real thing. Dress as you plan to, use props (if you intend to use them), and act it out as you intend to.

Epilogue

In Part 1, we introduced you to some characters at a business dinner. Some were likely recognizable. We imagine the scene was familiar, too.

The power of a story is that it taps the memories, experiences, and imagination of your audience. It builds a connection between the speaker and the audience and can pave the way for a far more effective presentation.

That’s because stories, as well as anecdotes, case studies, and analogies, are stickier than abstract concepts, particularly for audiences that lack a depth of knowledge in your topic. They serve as easy memory hooks that draw audiences to your message.

As Annette Simmons points out in her book, The Story Factor:

“When someone can connect to you through your story, they make a decision that at some level you are just like them. Whether it is because you think like they do, value the same things, or feel the same feelings, the similarity is enough to generate a feeling of trust. Once you can make this connection, the trust you create will accelerate your ability to influence and persuade those who feel connected to you.”

This is the end of our story about how you can tell your story.

The next chapter is up to you.