Public Speaking Report 1: The Six or Seven Types of Stories (Part 1)

As you eye the clock above the exit door, you wonder what you did in a former life to get stuck next to this guy. Five stories in, he’s still the hero of all his tales – vanquishing colleagues who put up roadblocks, coming up with ideas that blew the minds of all who heard them.

The rest of the table is largely eating in silence.

You look longingly toward the table in front of you. You wonder how they will ever get through their stuffed chicken with so much chatter and laughing going on. They are under the spell of a couple of great storytellers. How could one table get two? And, more importantly, why didn’t you sit at that table?

You usually nail it. There hasn’t been a business dinner yet where you didn’t size up the crowd just right. You think, “Why have I suddenly lost my touch?”

The story we just told is certainly not set to become a classic, but it is an example of how a story – with the right elements – can draw an audience into the message you want to tell. We are a species that enjoys a good story.

Literary scholars and researchers have increasingly delved into the intersection of story and evolutionary development of humans. They have many questions: Why have certain types of tales endured for millennia, sometimes in original form, other times repackaged and retold? Is there a connection between story and how our brains and behavior have evolved? Why are we a storytelling creature? Finally, why do we have such a rich imagination?

We’ve consistently witnessed stories that captivate audiences in memorable and meaningful ways. Powerful narratives inform, educate, persuade, motivate, and influence audiences in ways that help messages stick – which is what you, as a speaker, are hoping to accomplish.

Are stories, in any of their forms – anecdotes, case studies, analogies or flat-out narratives – in your public speaking toolbox? Read on to learn why stories are powerful, why you should have more than a few in reserve, and how you can better share those tales.

The Power of a Great Story

Let’s pause for a moment and think about how stories impact your own life. Here are a few questions to ask yourself:

- Have any helped you to gain a better understanding of your world, including your own motivations, as well as those of the people around you?

- Have you used a story to rewrite social norms or expectations, casting as main characters the “real-life” people who are at a disadvantage or have been marginalized?

- Do stories provide you with a literary stress test or rehearsal for the real thing? As you live vicariously through the characters and their messy lives, does it leave you space to explore and experience the trials, tribulations, and joys of life without real-life ramifications?

As Joseph Carroll, a professor of English at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, who has studied and written numerous papers on evolution and literary theory, puts it:

“(Imagination) signifies an interactive set of mental operations that include discursive reason, representation, symbolic imagery, aesthetic form, and emotional responsiveness. Working together, these operations produce emotionally charged mental images that significantly influence human behavior.”

In other words, we don’t even have to see something for it to affect our behavior. We just need to imagine it. A storyteller helps us to get there.

Effective storytellers put those pieces together for the audience and offer a conclusion. If done well, the audience will reach that conclusion themselves, not because they were directed to do so. Your story naturally led them there. Stories are memory hooks that draw audiences to your message, rather than aggressively roping them in.

Story adds emotional content and sensory details to your message that can make it easier for your audience to remember. When you give them a memorable story, they return to it again and again, long after you told it.

How can you, as a speaker, become a better storyteller?

Chapter I – Tell Us a Story

Allow us to set the scene: Our eyeballs are largely glued to a screen for most of the day, with U.S. adults spending ten-and-half-hours a day interacting with media. That includes TVs, smartphones, tablets, radios, smartphones, computers, and TV-connected devices, according to The Nielsen Company. Other surveys say adults spend several hours every day just watching television.

Whether you tune in to the nightly news, a reality show, a sitcom, an advertisement, or even a how-to series, you are going to find storylines aimed at grabbing your attention.

Given we are awash with so many images and stories, you might think:

“Why would anyone want to listen to one more story?”

Well, millions do. Last year, 675 million books in print were sold in the United States – a figure that doesn’t include ebooks or audiobooks. For every author who thinks a story has already been told, there is another author refreshing a familiar tale to great success.

In his book, The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human, Jonathan Gottschall looks into insights from biology, psychology, and neuroscience to try and understand why humans are attracted to stories. As he puts it:

“Human minds yield helplessly to the suction of story. No matter how hard we concentrate, no matter how deep we dig in our heels, we just can’t resist the gravity of alternative worlds…. We come in contact with a storyteller who utters a magical incantation (for instance, “Once upon a time”) and seizes our attention. If the storyteller is skilled, he simply invades us and takes over. There is little we can do to resist, aside from abruptly clapping the book shut.”

He further theorizes:

“(Story is) a powerful and ancient virtual reality technology that simulates the big dilemmas of human life.”

That theory speaks to a story’s power to connect with others who are also experiencing the dilemmas (and joys, too) of life. Good storytellers use story to create connections with their audiences to share goals, call for action, alter perspectives, or seek change.

Chapter Two – The Stories that Matter

Can stories get us to act?

This has been a central question in the research of Dr. Paul J. Zak, who has long studied the neuroscience of human connection, as well as the power of storytelling to change attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. The research suggests that an emotional story fires up certain parts of the brain, boosts certain neurochemicals, and causes people to act.

Basically, a good story grabs us and keeps our attention front and center on the story. Once hooked, we become emotionally engaged and are, in a sense, transported into the story. In some instances, such literary travel translated into action. Participants in two studies donated toward causes after watching video narratives that introduced dramatic stories with compelling characters.

Zak notes:

“Narratives that cause us to pay attention and also involve us emotionally are the stories that move us to action …. More generally, stories with a dramatic arc fit the requirements for high-impact narratives. This structure sustains attention by building suspense while at the same time providing a vehicle for character development. The climax of the story keeps us on the edge of our neural seats until the tension is relieved at the finish.”

There’s a bonus: The researchers found that if you audience “lives” within your story, they can recall the story a week after hearing it – a boon for any message the story helped to tell.

So, let’s dive into the story, or more specifically, your story, the one you will employ to share your key points. Because a story needs a framework, we begin with the plot.

Chapter Three – What’s the plot?

Let’s get on with it already!

In 2016, researchers at the University of Vermont’s Computational Story Lab released the results of a data mining experiment that reached deep into the well of human creativity. After looking at thousands of stories on Project Gutenberg, an online collection of more than 50,000 digital books, and crunching the numbers, they concluded there are only six types of stories in the world.

Those six stories, or plots, they said, could be found in stories of antiquity, as well as present-day blockbusters. The main character moves along one of the following arcs:

Rags to Riches – The main character gets to shed those rags for some posh threads, so to speak.

Real-life application: This can be a particularly powerful emotional arc to use if, as a speaker, you want to share your tale of rising out of poverty, being underestimated by many, and – despite that – finding success in a field that initially threw up obstacles for entry.

Riches to Rags – A powerful person falls in standing and fortune.

Real-life application: This can be a powerful emotional arc in reverse. If you, as the speaker, have suffered a fall from grace, then you can deliver a particularly powerful talk. You can use this experience as a springboard to talk about the importance of changing your perspective to the things that really matter, or adjusting your priorities.

Man in the Hole – the main character falls, but then rises (as opposed to rags to riches, a main character falls by getting into trouble, but gets out of it).

Real-life application: Given this arc is a bit of a cautionary tale, it could provide a way to frame a main message that not everyone is perfect. Sometimes we make a mistake, and, with luck, or some other fortunate intervention, we can get ourselves out of a bad situation. For example, you are an entrepreneur who is going to give a talk about how you went from working for someone else to running your own company. Maybe you made a mistake or two along the way. Maybe, you found yourself in the hole. Share how you got there, but most importantly the fortunate circumstances that helped you to crawl out.

Icarus – Named for the character of Greek stories who flew too close to the sun, this story tells the tale of a hero who rises and then falls.

Real-life application: This is a tale well-suited to warning an audience about the dangers of not recognizing the perils or dangers that face them – despite information to the otherwise. It also provides an illustration of how pride and an unrealistic view of your own abilities and talents can cause a project to fail.

Cinderella – Again, named after an enduring tale, this plot tracks the main character’s rise, fall, and then rise. As opposed to the “man in the hole” scenario, this fall is of no fault of the main character. It’s a matter of having to play out the bad hand that has been dealt them.

Real-life application: You don’t always have to employ a similar story with this arc. A CEO could use this arc to deliver a message to employees that she wants the company to break out of what they have always done – toil away in the shadow of bigger companies in their field. She’s ready to invest some money in a campaign to launch a new product. It’s time to go to the ball, she says, and see where that exposure takes the company. She believes the market will see the product as the perfect fit for their needs. Cue a life happily ever after future, with nary a glass slipper in sight.

Oedipus – Perhaps you read this in high school English? If you know the tale, life doesn’t look good for the main character at the start, but then things seem to turn around for a bit, only to unravel by the time the last word appears on the page.

Real-life application: This story is largely about what happens when one attempts to outwit fate. Fate is a powerful theme in and of itself. Perhaps you could use this as a springboard if you are talking to a group you hope to inspire to defy the low expectations others have put upon them. The idea being this: There is no “tricking” fate. You create your own future when you do the hard work of believing in yourself and trusting that your decisions are the right ones for you. The theme also could inspire the message of the dangers of thinking you can predict the future when the only control you really have is how you act in the present.

The Story Lab’s work was a new answer to an the old puzzle: How many stories are there in the world?

The Story Lab’s work was a new answer to an the old puzzle: How many stories are there in the world?

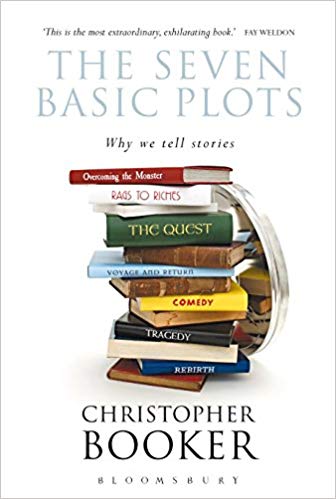

Another recent attempt to proffer an answer came in 2006 from Christopher Booker, a longtime British journalist and author, with his book, “The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories.”

They are:

Overcoming the Monster – A hero must head out on a long, arduous, hazardous journey to come face-to-face with the terrifying, seemingly all-powerful monster. After a series of barbs, and “taunting exchanges,” the hero and monster engage in a battle royale. The hero is woefully underwhelming, until, by superhuman strength, the hero manages to vanquish the monster. Peace is restored and the hero returns.

Rags to Riches – the “Ugly Duckling” of story archetypes, this is the tale of a character who is largely written off by many, only to experience a magical intervention or transformation that allows him or her to step into the spotlight – suddenly exceptional.

The Quest – Somewhere, well beyond the rolling green hills, city apartment, or middle-class home where the main character has been living life, there is a prize to be had. We are talking about a “priceless goal … a treasure … a promised land; something of infinite value” that is worth more than the dangers and perils the hero will inevitably come across in the pursuit for the treasure. It need not be an object, by the way, it could simply be the desire to come home.

Voyage and Return – Make no mistake: This is not the same as the Quest. Rather, it’s the story of a hero (or perhaps a clutch of characters) who take to the familiar path only to find that their steps have led them to a new world whose mores and norms are unfamiliar to the world they left – are unable to return to. Soon, there is a threat – the kind of threat that makes the hero or group of travelers extremely uncomfortable. After what is typically an involved escape, they return to the well-worn path where their journey began.

Comedy – As Booker puts it: “Comedy is a very specific kind of story. It is not simply a story which is funny.” Rather, it is a plot device that introduces a kind of chaos – mistaken identities, disguises, embarrassments, misunderstandings, and “improbable concoctions” that, phew, get resolved successfully and happily before the last word is read or uttered. Crucial to this plot is that a character experiences a transformation into a “new and improved” version that has shed negative traits or actions. Anything that was dark or muddled becomes light and clear. If a character persists in some evil ways, they are simply banished or punished so as not to spoil the fun.

Tragedy – A hero is drawn into behavior that is dark, antisocial, immoral – add whatever word in here that suggests a good guy, or simply a normal guy, goes bad. Initially, it appears that bad guys can finish first, as the main character seems to achieve what he is looking for with his or her ill-gotten gain. But that world starts to crash when disillusionment and frustration arise. Soon, things are out of control. There is no transformation, no change of heart, and the hero hurtles towards his or her own destruction, often causing others tragedy along the way.

Rebirth – The main character gets a raw deal – what should have been a great life goes astray because of a spell, poor upbringing or an unjust act. Whether by incantation or a bad break, the hero enters a frozen state – a living death. In today’s vernacular, he or she is just going through the motions – isolated from society. That is until love shows up. The thaw is sometimes gradual; other times the ice cracks. Miraculous redemption ensues.

Then, there is the 1919 writing manual from Wycliff Aber Hill, Ten Million Photoplay Plots, which presumably helped struggling screenwriters retreat from the lip of the abyss of a blank page. Any good story has a bit of exaggeration, but Hill (or his publisher) wildly overplayed the title’s promise. He only offers 37 basic plots. However, they offer another source of inspiration if you are looking for how to frame your story. Have a peek.

The late, bestselling American author Kurt Vonnegut had his own theories, too. In 1995, he offered a few:

As you can see, if you are not a natural storyteller, you must not despair. Drenched as we are in narrative, even the experts in the field need some guidance as to how to create compelling stories that get deep into the minds of readers.

Sharing Your Story – Tip No. 1

Stories are guided by a plot, also known as a sequence of events. That plot is typically plugged into a format that breaks the story into five parts. They are:

Exposition – The reader is put into the story. Characters are revealed and developed. The scene is set. The conflict is revealed.

Rising Action – The pace picks up, as challenges and obstacles begin to get thrown before the main character. Conflicts build and complications arise.

Climax – This section signals the turning point. The suspense that has been building peaks and fallout is eminent.

Falling Action – The story begins to fade into the sunset. Mysteries are solved (or left unsolved) and fictional strings are tied up.

Denouement or Resolution – It’s time to take a breath and reveal the outcome of the story. The hero returns, the hero is transformed, or the main character is banished, for instance. This is the place an author may reveal a moral or lesson.

You may have already lived some of the plots listed above, or known others who have. Identify the elements of those stories and then plug them into a traditional story structure.

Here are some examples:

- Personal Experience – Your quest didn’t take you deep into Middle Earth, but it did bring you deep into the academic buildings where you earned your master’s degree. Was there struggle? Were there obstacles and challenges that could have derailed your progress? Identify and expand on the drama and conflict in everyday events as you tie that experience to your main message.

- Anecdotal Evidence – Do you have a friend who lost nearly everything and then gained it all back? Research has shown humans tend to be particularly attentive to stories that suggest a struggle that ends in a happy ending. This plot works well if you are trying to persuade an audience that needs a dose of hope.

- Case Studies – Look at your supporting material. Is there a story lurking in one of the case studies that could be mapped out like a plot? Such an example could reveal the tragedy of not implementing a service or program, for instance.

The News – Whether in print or on a screen, the news provides a steady stream of human tales, joyful and otherwise. Say you are a manager who is trying to implement a new program at work but are meeting with resistance. Perhaps you can find a topical story that offers a similar scenario – which resulted in success once the program was put into place. Sometimes, story provides a softer and less strident approach to persuading others to follow your lead.

The News – Whether in print or on a screen, the news provides a steady stream of human tales, joyful and otherwise. Say you are a manager who is trying to implement a new program at work but are meeting with resistance. Perhaps you can find a topical story that offers a similar scenario – which resulted in success once the program was put into place. Sometimes, story provides a softer and less strident approach to persuading others to follow your lead.

Chapter 4 – Who is my audience?

Your audience is a crucial part of this story. That’s the group you are hoping to persuade, encourage to act, or gain new knowledge. So, what is the one headline, idea, or takeaway message you want your audience to remember three months from now?

Further, the audience will better remember that message if it also aligns with their goals and values. You can learn more about this process here. Some questions to ponder when it comes to your audience:

- What do they value?

- How relevant is your topic to them?

- How much do they already know about your topic?

- How much do they need to know in order to accomplish your goals?

- Do they support your idea?

The answers to the questions you ask yourself and your audience are, collectively, the guiding light when it comes to picking your plot and developing the personality and motivations of your characters.

Sharing Your Story – Tip No. 2

Here’s an example of how that might work:

Say you are a town planner and an ambitious community center plan is facing delays. The last thing you want is the community to waver in its support. You need to offer to them an aspirational message that encourages them to imagine a time when the setbacks are but a memory.

Here’s a formula you could use:

- You decide to work with a case study of another project that faced similar delays.

- You flesh out the personalities that helped to keep the project on track.

- You incorporate them into an “Overcoming the Monster” or “Man in the Hole” plot scheme.

- You then stretch out the details over the traditional, five-part dramatic structure.

When it comes to influencing your audience, story provides you with some perks that say, bribery, does not. As Annette Simmons points out in her book, The Story Factor:

“Story is a pull strategy (rather than a push). If your story is good enough, people – of their own free will – come to the conclusion they can trust you and the message you bring.”

Let’s start loading up that story tool box.

Chapter 5 – Where do I find my story?

The easiest place to start is with the person you know best – you. However, there are plenty of sources that will help you to fill your well of potential stories.

Sharing Your Story – Tip No. 3

Your Aspirations – What are your future goals and where do you see yourself in the future?

Fiction – They say the greatest form of flattery is imitation. With a world awash in stories, there are bound to be dozens that resonated with you. You can bet they resonated with others, too. Look for myths, fables, parables, fairy tales, and tall tales that you can use wholesale or adapt.

Personal History – Fictional families don’t get to have all the fun. Your family history and the stories that passed through the generations offer a rich tapestry from which to pull a thread of a story.

Your Journal – Have you kept a journal or business diary? Day-to-day tasks and other commitments can jog a memory or thought. Personal recollections and observations can inspire a story.

Friends and Strangers – Listen to the stories of others and begin to file them away.

Walk Down Memory Lane – Look through old notes, old emails, yearbooks, photo albums – anything that might offer some tidbits about your past and prompt some memories.

“A-ha Moment” – Think about those moments in your life when advice or kindness from a stranger or mentor changed everything. And, you may not have known at the time! There’s the a-ha.

Media – Media in all forms is dripping with content. Squeeze a bit of it and you will undoubtedly pick up a handful of story ideas, if not outright stories you can adapt for your next presentation.

Chapter 6 – How do I start my story?

So, you have the pieces of the puzzle – plot, narrative structure, your main message, the goals and values of your audience, and places to turn for inspiration. Now, you bring those together to make your story work.

Sharing your Story – Tip No. 4

Here are some questions with which to start:

- What are you trying to achieve with your story?

- What story will best resonate with my audience?

- What pieces need to click together to create the story you want to tell?

- Is there more than one way to tell this story?

- Would several plot lines work?

We end Part I of the Power of Story with a call to action of our own. Over the next month to come, we hope you will take these pieces and begin to solve the puzzle.

When we return, we will offer up more tips and techniques on how to take that story to the next level. For instance, you will learn how to best tell your stories, how to best utilize your stories, and how best to assess if your message rang through loud and clear.

See you next month ….

“Human minds yield helplessly to the suction of story. No matter how hard we concentrate, no matter how deep we dig in our heels, we just can’t resist the gravity of alternative worlds…. We come in contact with a storyteller who utters a magical incantation (for instance, “Once upon a time”) and seizes our attention. If the storyteller is skilled, he simply invades us and takes over. There is little we can do to resist, aside from abruptly clapping the book shut.”

“Human minds yield helplessly to the suction of story. No matter how hard we concentrate, no matter how deep we dig in our heels, we just can’t resist the gravity of alternative worlds…. We come in contact with a storyteller who utters a magical incantation (for instance, “Once upon a time”) and seizes our attention. If the storyteller is skilled, he simply invades us and takes over. There is little we can do to resist, aside from abruptly clapping the book shut.” The News – Whether in print or on a screen, the news provides a steady stream of human tales, joyful and otherwise. Say you are a manager who is trying to implement a new program at work but are meeting with resistance. Perhaps you can find a topical story that offers a similar scenario – which resulted in success once the program was put into place. Sometimes, story provides a softer and less strident approach to persuading others to follow your lead.

The News – Whether in print or on a screen, the news provides a steady stream of human tales, joyful and otherwise. Say you are a manager who is trying to implement a new program at work but are meeting with resistance. Perhaps you can find a topical story that offers a similar scenario – which resulted in success once the program was put into place. Sometimes, story provides a softer and less strident approach to persuading others to follow your lead.