The Statistic Communications "Experts" Keep Getting Wrong

In dozens of books and hundreds of articles, you’ll find media trainers, presentation coaches, and communications experts offering a startling statistic:

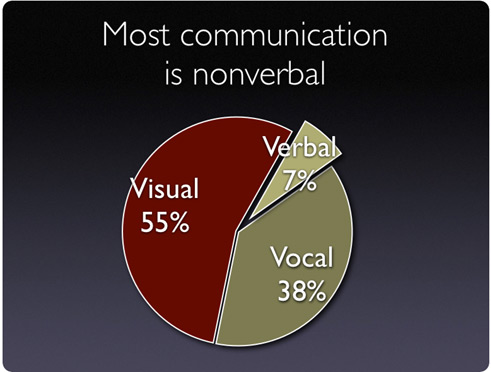

Only 7 percent of the way someone forms an impression of you comes from your words! The remaining portion comes from your voice (38 percent) and your body language (55 percent)!

There’s only one problem: Those statistics are wrong. Completely wrong.

Their root comes from a 1960s study by a UCLA professor named Dr. Albert Mehrabian. But Mehrabian never intended for his research to be used—or misused—that way.

Mehrabian’s study was very limited in scope—it looked only at single words, focused solely on positive or negative feelings, and didn’t include men—and yet, I see articles at least once a week touting these numbers as gospel, as if they have much broader implications than they actually do.

Had these communications “experts” taken the time to look at the original research (or simply look at Dr. Mehrabian’s Wikipedia page, which debunks this myth), they wouldn’t have made this mistake. So I can only conclude that communications professionals who use this data are ignorant, lazy, or willfully misusing this data to sound smarter than they are.

As an example, I came across a video from Stanford Business Professor Deborah Gruenfeld last week. I saw the video because it was a “Sponsored Post” on Twitter. The link led me to a YouTube video, which had this in the video description:

“When people want to make an impression, most think a lot about what they want to say. Stanford Business Professor Deborah Gruenfeld cautions you to think twice about that approach. The factors influencing how people see you are surprising: Words account for 7% of what they take away, while body language counts for 55%.”

Wrong!

In the video, Gruenfeld says:

“When people are forming an impression of you, what you say accounts for only seven percent of what they come away with.”

Wrong!

Creativity Works, a U.K.-based communications firm, produced this video called “Busting the Mehrabian Myth.” It’s a well-produced (and humorous) video. UPDATE: Several readers have correctly pointed out that this video goes too far in the opposite direction, prioritizing words over delivery. That, too, is wrong — the right balance of words and delivery is highly contextual, and it’s too reductionist to say that one generally matters more than the other.

Have thoughts about body language and the Mehrabian Myth? Please leave them in the comments section below.

The PowerPoint slide in this post comes from the Presentation Zen website; to their credit, they acknowledged that this graphic isn’t quite right.

The real problem with this is that people want to take the interpretation to the extreme polar opposites. Those that are addressed in this video, and those who want you to believe that there is ZERO relevance to the study.

Bottom line is that your non-verbals CAN influence your message (not always WILL, but CAN). When your non-verbals send a different message than your verbals, your audience can be confused, interpret an unintended message, or miss your intened message completely because they’re more focused on your awkward facial expressions or body posture. It happens, and to ignore this is irresponsible.

Non-verbals CAN BE just as important as the words you speak. Non-verbals CAN detract from your spoken message. Non-verbals CAN leave your audience with a different message than what you intended.

You don’t need a fancy scientific study to know that.

Ken,

Thank you for your terrific comment – you and I are in complete agreement. Here’s how I addressed this issue in my book, The Media Training Bible:

One day, I’ll write a second edition of the book. When I do, I’ll drop the Mehrabian reference entirely. Even though I couched the study accurately, there’s just too much confusion around the study for it to be useful.

Thanks for reading the blog!

Brad

Rick’s comments are spot on. Especially in corporate environments where lawyers exert considerable sway over what’s written, it’s up to the communication pros to remind whoever reads those words that HOW the words are read is important too.

Brad, you simply need to delve deeper… Mehrabian’s 1968 findings have validity when applied to prepared content and not to interactive dialogue (conversation), but not formerly researched until 20 years later. Examine researchers who followed Mehrabian, specifically Trimboli & Walker (1987), and you will see that the “statistics” positively correlate to prepared content, based on predictability and “camouflage”.

The “experts” are not necessarily “wrong”, they are merely uninformed as to how to apply the findings to the proper type of communication (planned or spontaneous).

When the level of camouflage is higher, the nonverbal and verbal components of communication are relatively equal. In spontaneous conversation, each participant can alter the topic or flow at any point (a highly unpredictable setting), raising the level of camouflage.

However, when content is prepared or planned, the nonverbal cues dominate to the levels identified in earlier studies, such as Mehrabian’s. When the intent is to increase communication clarity, the sender purposely delivers a message that has little or no camouflage. This allows receivers to focus less on clarity in words and more on the implied meaning behind those words (body language, intentions, etc.).

High predictability in prepared content is consistent with nonverbal dominance. The more you “plan” what to say, the lower the camouflage (hidden meaning) in words — which is where a “7%” figure shows up. But do not associate the small percentage with unimportance. It has to be the right 7% for the message to have impact.

This leaves the balance (the 93% figure) in the nonverbal cues associated with that 7%. Distractions in actions (excessive movements, haphazard gestures), vocal inflections (verbal fillers, speed of speech), facial expressions, etc. will be more noticed. Therefore, highly predictable body language (less distractions) allow clearly developed messages to achieve a planned objective (intention).

Unfortunately, you failed to identify the underlying reasons as to what causes nonverbal dominance with respect to the context of the communication (planned or unplanned). Assuming you are an “expert”, I would not categorize you as “ignorant, lazy, or willfully misusing this data”, just because you didn’t do your homework — but I suggest that your perspective is relatively “less informed”.

If one looks into the academic literature, and further examines the experiential data from global observers (as I have been lucky enough to be part of for many years), one would clearly see why nonverbal cues dominate in prepared speech and how the early findings of Mehrabian (and others like Nierenberg, Friedman, etc.) are substantiated in later studies that focus on causation and not just effect.

Hi Tom,

Thank you very much for reading my post and leaving such a thoughtful comment.

I understand the point you’re making, but if anything, the fact that it took you eight paragraphs of nuance–along with citations–to make your point only underscores the point I made in this article.

The core of my article says this: It is inaccurate to make an overly generalized statement that “Only seven percent of what people take out of your communications is your words.” As you indicated in your comment, that percentage relies on a lot of other factors and changes depending on the context. It simply cannot be made as a blanket, over-arching statement covering any communications situation that occurs anywhere, anytime. In the Stanford video I alluded to as an example, that’s exactly how they used it.

Stanford isn’t alone, of course. Do a quick search on line, and you’ll find hundreds of self-proclaimed experts who claim that 93 percent of body language comes from vocal cues and body language. They claim that as an absolute rule, covering all types of communications situations. As you stated in your comment, that’s simply not true.

Unless social science validates that only seven percent of communications occurs through words regardless of the context in which the communication occurs (and I doubt it ever will), it will remain inaccurate to make such a blanket statement without the type of nuance you added.

Thanks again,

Brad

This article really brought me up short as I am one of those “experts” who has quoted the Professor Mehrabian statistics in my workshops and speeches and book. It gave me a lot to think about and it was helpful to read the other comments left here, with your responses.

I’ve decided I will continue to use the bar graph of the percentages of words–tone of voice–body language, but I will be more careful to explain the whole thing more completely. For that I thank you.

When I use it in my workshops, I always tell people that their words are incredibly important. Helping them develop sound key messages is a major part of how we spend our time — for good reason. But the whole subject of nonverbal communication is extremely important for them to understand as well because what they do with their feet, hands, face (especially eyes) and voice can either contradict or support their words. We spend time working on this — and I give them feedback on these things during our role-play critiques — because most people I work with have not paid enough attention to these subjects previously. They need to understand the importance of how the words they say are received and believed. The bar graph makes a memorable point to those who were of the opinion that all that mattered was what they said, not paying much attention to how they said it. A good balance is critically important.

Hi Judy,

Thank you very much for your comment.

I have a confession to make. My sarcastic quote marks around the word “expert” aside, I was equally as guilty of using this statistic in the wrong way. I discovered my error a couple of years ago, and wrote a post in mid-2011 pledging to banish it from my presentations from that point forward. So my sarcasm could have been applied to myself circa 2011, and fairly so – I should have done a more serious look at what the numbers meant before parroting them without much thought.

I really appreciate the humility of your response, and assure you that we’re all in good company here. Together, we’ll help eradicate the misuse of this statistic!

Best wishes,

Brad

I think it depends. Sometimes, with certain people, the non-verbal communication is more important. Other people say what they mean and mean what they say. I have been turned off by people who knew the words to say, but had a poor non-verbal presentation. That nullified the effect of their words.