How To Be (And Why You Should Be) Skeptical Of Your Facts

Facts are funny things.

Sometimes, we interpret them in a way that seems so obvious to us that we don’t even consider how someone could possibly view them differently.

That’s why it’s a good idea to go through the facts in our presentations, try to view them as a skeptical, adversarial, or plain intellectually curious audience member might, and address any unhelpful interpretations before they take hold.

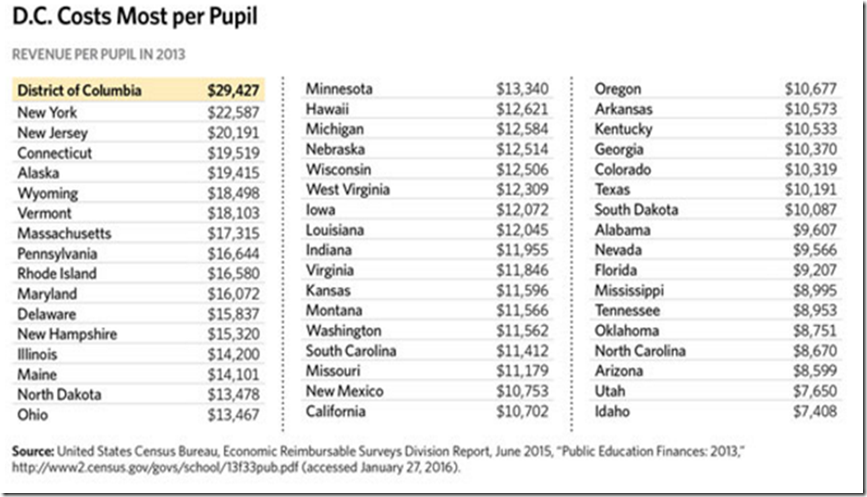

As an example, I recently worked with a speaker who projected the following slide:

In his mind, the takeaway was obvious: Washington, DC spends far more per student than any U.S. state and doesn’t get nearly enough in return for its investment.

But as I examined the slide, I couldn’t help wondering:

What would happen if Washington, DC didn’t spend that much money per student? Would already low-performing schools get even worse?

Is Idaho spending enough money per student? Maybe this chart actually shows the under-investment of the states in the third column?

Why are most of the states in the third column located in the American south and west? Are states in the eastern part of the country generally more committed to per-pupil spending?

The speaker didn’t want me to interpret the data that way. But by popping this slide on the screen and assuming my takeaway would be identical to his, he lost control of his message.

There’s a small fix. After showing this slide, he could add:

“Now, you might be wondering if Washington, DC’s results would be even worse if they spent less, or if Idaho would be better served by a more generous budget. As you’ll see in a few minutes, there’s not a strong correlation between per-pupil spending and results.”

That short addition would have eliminated—or at least forestalled—my skepticism, leaving me open to hearing his next point without resistance.

You can find two more examples of raw facts that were improved with additional context in a post I wrote a couple of years ago called “Say This Ten Times: I Am Not a Wikipedia Page!”

Brad, there is a much larger problem with this slide than merely an issue of skepticism. It concentrates on data rather than information. The second you project a slide like this, the audience stops listening to you. They attempt to read and interpret all the data. “Where’s my state in the list?” “What constitutes a good amount versus a bad amount?” “Why does the title say COSTS while the subtitle says REVENUE?” “What is that tiny text at the bottom? Are you trying to hide something?”

The slide isn’t making a point. It is merely presenting a data dump. The individual amounts are irrelevant to the point the speaker needs to make. Think how much more meaningful and impactful this would be if the data were presented as a cluster chart of points on a simple Y-axis with three tick-marks: $7500, $15000, $22500. No other numbers. DC gets the only label and stands out as a clear outlier with a big textbox saying DC: $29,427. All by itself, far above all the other state dots. Then make the slide title a clear statement of the point the speaker wants to make. Suddenly the informational content can be consumed at a glance and the audience can go back to listening to the presentation from the speaker.

The fact that the source data appeared in tabular form in the original report is irrelevant. Don’t be a slave to your data sources. They only provide the raw materials for the points you want to make.