Sorry, But You’re Not "Better When You Wing It"

Every so often, speakers resist my advice to practice for an interview or presentation, claiming that practice robs their talks of spontaneity and reduces their performance. They insist that they’re “better when they wing it.” It’s tempting to tell them they’re wrong—and they almost always are—but I thought I’d turn this one over to a few familiar names.

SWIMMER MICHAEL PHELPS

According to Discovery Health, “He’s usually at the pool by 6:30 am where he swims for an average six hours a day or around 8 miles per day. He swims six days per week including holidays.”

Ma tells The New York Times that: “Practicing is about quality, not quantity. Some days I practice for hours; other days it will be just a few minutes. Practicing is not only playing your instrument, either by yourself or rehearsing with others — it also includes imagining yourself practicing. Your brain forms the same neural connections and muscle memory whether you are imagining the task or actually doing it.”

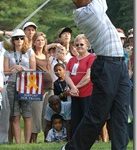

BASEBALL ALL-STAR ROY HALLADAY

BASEBALL ALL-STAR ROY HALLADAY

According to Business Insider, “Cy Young award winning pitcher Roy Halladay is one of the hardest working men in baseball. According to Sports Illustrated, he routinely puts in a 90 minute workout before his teammates make to the field.”

I attribute people’s reluctance to practice to one of four things: insecurity, fear, arrogance, or (most typically) a genuine but misguided belief that they’re better without it. I understand why they might have reached that conclusion: practice can feel uncomfortable and unfamiliar, and it’s that very lack of familiarity that convinces people that they’re better off-the-cuff.

But unless you’re a better speaker than Phelps is a swimmer, odds are you can benefit from practice. As Yo-Yo Ma suggested, the goal is to develop muscle memory through practice that automatically guides you when you hit the stage.

“At a tournament, I don’t really spend a whole lot of time there on the range, or even on the putting green or anything like that. When I get to a tournament site, I feel like my game should be ready. That’s one of the reasons why I don’t play as many weeks as a lot of these guys do, because I spend a lot of time practicing at home. I do most of my preparation at home. Once I’m at a tournament site, I’m there just to find my rhythm, tune up a little bit, and get myself ready to go play the next day.” – via Human Kinetics

When I watch people practice their presentations, we often uncover a few soft spots. It could be an abstract point without the rich supporting material that makes it more memorable. It might be an awkward transition. It may be a visual that interferes with the spoken delivery. Those gaps cannot be identified without practice, and the “off-the-cuff” speaker usually ends up committing those otherwise preventable errors while standing in front of an audience.

The quality of practice is imperative, though, and too much practice can be a bad thing. This post offers some tips on how to practice for a media interview. How to practice for a speech or presentation while keeping the material fresh for you as a speaker will be the focus of a post soon—but in the meantime, here’s one tip: pay close attention to the transitions between points, as that’s often a place where everything falls apart.

All images from Wikimedia Commons. Michael Phelps in public domain; Yo-Yo Ma by Sam Felder; Roy Halladay by Keith Allison.

Like the blog? Read the book! The Media Training Bible: 101 Things You Absolutely, Positively Need to Know Before Your Next Interview is available in paperback, for Kindle, and iPad.