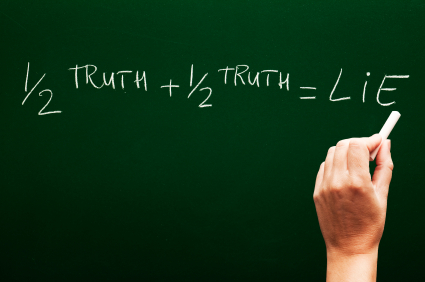

What Do You Think? Is This "License" or a Lie?

When you’re giving a speech, is it okay to embellish your humorous anecdotes to make sure they don’t land with a thud?

James C. Humes, author of the popular public speaking book Speak Like Churchill, Stand Like Lincoln, says yes. He argues that humor, when delivered in the third person, can take the audience out of the moment. He writes:

“When you start by saying ‘this salesman’ or ‘this psychiatrist,’ you have already signaled the audience that this is a joke—something that didn’t really happen—and you have already lost them. Lead them by the hand into your story by saying, for example: ‘An old woman in the town I grew up in’ or ‘A lawyer I know once had a client walk in…’”

Humes believes that such stretches of the truth can be considered “humor license,” similar to the “dramatic license” audiences grant to stage actors. During a speech, Humes writes, “You’re not under oath…don’t worry about stretching the truth.”

But is he right? Is stretching the truth during a humorous anecdote a reasonable use of “license,” or is it simply a lie that could threaten a speaker’s credibility?

If “lie” seems like a strong word, consider this piece of advice from Humes: “Once you repeat it a few times in your own style, you begin to believe that it really did happen.”

A quick anecdote (and I swear, this one is true). During my presentations, I used to tell a story about “a client in Georgia.” The client didn’t really exist—it was a composite of several different clients. But after my presentations, a few people came up to me and asked me who that client was. It made me feel dishonest. Since then, I’ve made it clear to audiences that the “client” is a fictional example. And you know what? The story hasn’t lost any of its zip.

Humes is a former speechwriter for five presidents. The men he served—Eisenhower, Nixon, and Ford among them—served in an era that allowed more license for humorous anecdotes. Today’s politicians have their speeches fact checked, blogged and tweeted about, and dissected for accuracy by opposition researchers. The license Humes recommends may not be fully dead, but it’s dying. And it could come with a great risk to people’s reputations as straight shooters.

My suggestion? Know your audience. Assess whether “humor license” would be well-received or place your reputation in the hands of nefarious opponents and journalists looking for a sexy headline. And don’t take it at face value that audiences will automatically grant you humor license.

[poll id=”30″]